A New Ray of Hope: Low-Dose Oral Minoxidil Revolutionises Hair Loss Treatment

Hair loss, an issue plaguing millions globally, finds a new contender in its treatment arsenal. Low-Dose Oral Minoxidil (LDOM) is emerging as a promising alternative. It has shown efficacy in treating various hair disorders while sidestepping the drawbacks of its topical counterpart.

Understanding the Prevalence of Hair Loss and the Challenges of Treatment

Hair loss, medically referred to as alopecia, is an extremely prevalent condition, affecting a significant number of individuals globally. On a global scale, an estimated 85% of men and 33% of women will experience some form of hair loss at some point in their lives. More specifically, by the age of fifty, approximately 85% of men will have signs of thinning hair, and more than half of women may experience hair loss in the post-menopause period. Furthermore, an estimated 25% of men experiencing hair loss begin this process before they reach the age of twenty-one.

Minoxidil has been a popular choice for years as a topical treatment for both men and women to treat hair loss. Its primary role is to stop hair from falling out.

The Emergence of Low-Dose Oral Minoxidil

LDOM is gaining momentum for its well-tolerated and effective role in treating hair disorders. A review in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology heralds LDOM as a promising treatment, especially for normotensive patients who find topical solutions troublesome.

Initially synthesised as an antihypertensive drug, oral Minoxidil gained attention in the treatment of hair loss due to clinical trials observing hirsutism and hypertrichosis as side effects. Currently, researchers are investigating the use of topical Minoxidil for treating different hair disorders such as androgenetic alopecia, telogen effluvium, and scarring alopecia, among others.

The pioneer in investigating LDOM for hair loss is Dr. Rodney Sinclair, Professor of Dermatology at the University of Melbourne. “Oral minoxidil is already widely prescribed by dermatologists to treat hair loss worldwide,” he explains.

Women generally require lower doses, ranging from 0.25 to 2.5 mg/day. Men benefit from doses between 2.5 to 5 mg/day.

The FDA had approved topical Minoxidil for treating male and female pattern hair loss in the late 1980s and early 1990s, but the oral form remains off-label. Many studies have shown LDOM to have success rates higher than 65%.

How Does Minoxidil for Hair Growth Work?

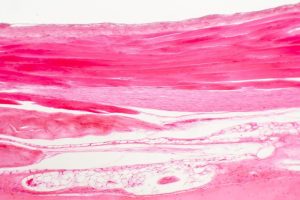

The mechanism of Minoxidil in stimulating hair growth is not entirely known. However, Dr. Sinclair explains that animal studies indicate Minoxidil prolongs the anagen phase, reduces hair shedding, increases fibre diameter, and reverses hair miniaturisation by increasing the uptake of amino acid cysteine into the hair bulb outer root sheath. This transport is crucial in hair keratinisation and growth.

Minoxidil, when applied directly to the scalp, works in several ways to stimulate hair growth. A scalp enzyme called sulfotransferase converts minoxidil into a salt called minoxidil sulfate, which is a key mechanism in the process.

This active form of the drug operates by shortening the telogen, or resting, phase of the hair and inducing the hair to enter the anagen, or growing, stage. There is also evidence that minoxidil can enhance the thickness of the hair.

In addition, it functions through various other pathways, including acting as a vasodilator and an anti-inflammatory agent, and inducing the Wnt/β-catenin signalling pathway, which is crucial for hair growth. It also may affect the length of the anagen and telogen phases of hair growth. Those with higher sulfotransferase activity may respond better to Minoxidil treatment than patients with lower sulfotransferase activity.

Weighing the Side Effects

While LDOM circumvents some side effects of topical Minoxidil, it’s not without its own. Common side effects include pedal oedema, tachycardia, and generalised hypertrichosis.

Pregnant or lactating women should avoid using Minoxidil due to its potential teratogenic effects.

Key Takeaways

LDOM offers a new avenue for those grappling with hair loss. While not devoid of side effects, its efficacy in treating various hair disorders makes it an essential tool in the fight against hair loss.

Patients should be well-informed about Minoxidil therapy and closely monitored to tailor the treatment for optimal outcomes.

Disclaimer: The information provided in this article is for educational purposes only, and should not be considered medical advice. Please consult with a healthcare professional for more personalised guidance and various treatment options that may be available to you.

References

- McMichael, A. J. (2003). Ethnic hair update: past and present. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 48(6 Suppl), S127-S133.

- Lee, W. S., & Lee, H. J. (2012). Characteristics of androgenetic alopecia in Asian. Annals of Dermatology, 24(3), 243-252.

- Hogan, D. J., & Chamberlain, S. (2000). Alopecia in children. Seminars in Cutaneous Medicine and Surgery, 19(1), 37-42.

- Tosti, A., & Piraccini, B. M. (1996). Minoxidil. Dermatologic Clinics, 14(4), 739-744.

- Motofei, I. G., Rowland, D. L., Tampa, M., Sarbu, M. I., Mitran, M. I., Mitran, C. I., … & Bratu, O. G. (2021). Finasteride adverse effects and post-finasteride syndrome; implications for dentists. Journal of Mind and Medical Sciences, 8(1), 11.

- Dawber, R. P. R. (1990). Minoxidil and its use in the treatment of alopecia. Clinical and Experimental Dermatology, 15, 299–301.

- U.S. Food & Drug Administration. (n.d.). Minoxidil. Retrieved from [insert URL]

- Suchonwanit, P., Thammarucha, S., & Leerunyakul, K. (2019). Minoxidil and its use in hair disorders: a review. Drug Design, Development and Therapy, 13, 2777-2786.

- Rossi, A., Cantisani, C., Melis, L., Iorio, A., Scali, E., & Calvieri, S. (2012). Minoxidil use in dermatology, side effects and recent patents. Recent Patents on Inflammation & Allergy Drug Discovery, 6(2), 130-136.

- Cross, J. (2006, April). MEDLINE, PubMed, PubMed Central, and the NLM. Editors’ Bulletin, 2(1), 1–5.