Researchers have developed an experimental gene therapy that reduces pain by targeting specific brain circuits, potentially offering relief without the addiction risks linked to opioids.

For people living with chronic pain, relief often comes at a cost.

Opioids such as morphine can dull pain effectively, but they do so by affecting wide swathes of the brain. Over time, this broad impact increases the risk of dependence, tolerance, and other side effects. For many patients, pain relief and addiction risk are tightly entangled.

Now, research may have found a way around this dilemma.

A new preclinical study published in Nature describes an experimental gene therapy that reduces pain by acting only on the brain circuits responsible for pain processing, while avoiding pathways linked to reward and addiction.

The research was led by scientists from the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine and University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing, with collaborators from Carnegie Mellon University and Stanford University.

If the approach eventually proves safe and effective in humans, it could point towards a new way of treating chronic pain without the use of opioids.

How Do Opioids Work?

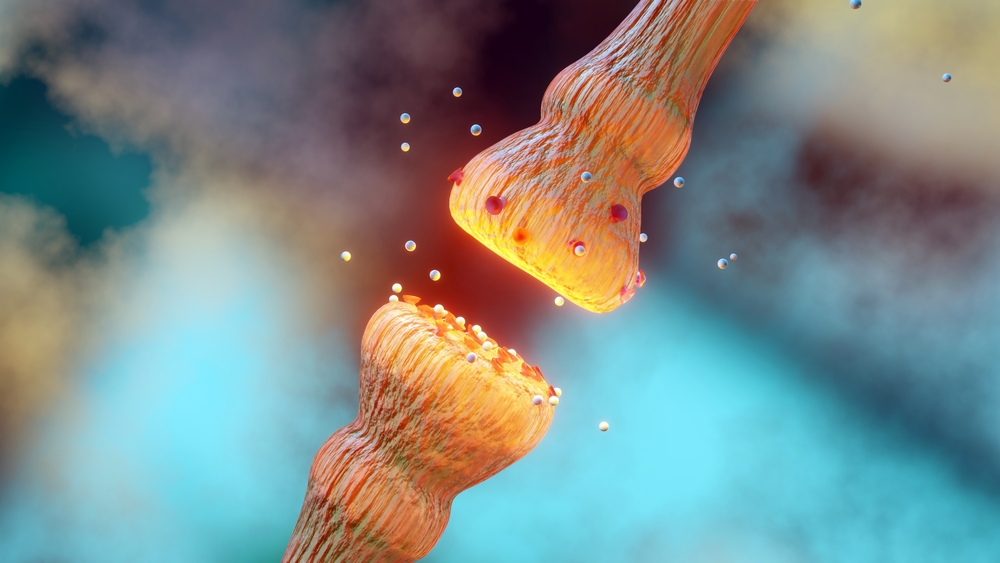

When the body experiences pain, specialised nerve cells send electrical and chemical signals from the site of injury through the spinal cord to the brain. These signals are then processed in several brain regions that determine not only how intense the pain feels, but also how distressing it is.

Opioids bind to μ (mu)-opioid receptors located throughout the brain, spinal cord, and gut. When activated, these receptors suppress the release of neurotransmitters involved in pain transmission, allowing fewer pain signals to reach the brain.

Opioids can be powerful painkillers as they do not only block pain at the source, but also dampen pain perception centrally.

Why Opioids Also Affect Pleasure and Mood

The problem is that mu-opioid receptors are not limited to pain pathways.

They are also concentrated in brain regions involved in reward, motivation, and emotional regulation. These same circuits play a role in reinforcing behaviours that the brain interprets as beneficial or pleasurable.

When opioids activate these reward pathways, they trigger the release of dopamine – the neurotransmitter often associated with pleasure and reinforcement. This produces feelings of euphoria or emotional relief, especially at higher doses.

Over time, the brain adapts. It becomes less responsive to the drug, meaning higher doses are needed to achieve the same effect. This process is known as tolerance. At the same time, the brain begins to rely on the drug to maintain normal function, which can lead to physical dependence.

The act of relieving pain while stimulating reward is what makes opioids uniquely effective, and uniquely dangerous.

According to Gregory Corder, PhD, assistant professor of psychiatry and neuroscience at Penn and co-senior author of the study, the aim was to break this link.

“The goal was to reduce pain while lessening or eliminating the risk of addiction and dangerous side effects,” he said. By targeting the precise brain circuits that morphine acts on, the experimental gene therapy looks to offer pain relief for those living in chronic pain while reducing side effects.

How Does Gene Therapy For Pain Work?

Using AI to Map Pain Precisely

To do this, the researchers first needed a clearer picture of how pain is processed in the brain.

Using advanced brain imaging, the team studied specific neurons involved in sensing and responding to pain. They then developed an artificial intelligence–driven system that could analyse natural behaviours in mice and generate a more accurate, objective measure of pain levels.

Using this AI-based platform, the researchers could measure not only the presence of pain, but also its intensity and the level of intervention needed to reduce it. That data became the blueprint for a highly targeted gene therapy.

Genetically Switching Off Pain Signals

The experimental therapy works by introducing a genetic mechanism that dampens the identified pain-related signals in specific brain circuits.

When activated in animal models, the therapy reduced pain for extended periods without interfering with normal sensation or activating the brain’s reward system. Importantly, it did not trigger behaviours associated with drug-seeking or dependence.

What This Means For Patients

Chronic pain affects tens of millions of people worldwide, yet healthcare systems often struggle to manage it effectively. Simultaneously, opioid misuse remains a major public health problem in many countries. The challenge of balancing pain relief with medication safety remains…

This gene therapy does not offer an immediate solution. Researchers are still years away from understanding its real-world impact. Even so, the study signals a shift in how scientists may design future pain treatments: towards more targeted approaches that reduce the risk of dependence and addiction.

If successful, such approaches could redefine pain management for millions living with chronic pain.

Moving forward, the research team is working with Michael Platt, PhD, the James S. Riepe University Professor, Professor of Neuroscience, Professor of Psychology, for the next phase of work as a hopeful bridge toward future clinical trials.

Reference

- Oswell CS, Rogers SA, James JG, et al. Mimicking opioid analgesia in cortical pain circuits. Preprint. bioRxiv. 2025;2024.04.26.591113. Published 2025 Apr 5. doi:10.1101/2024.04.26.591113